Nicolás Smith-Sánchez: Aquarelle aus dem Meer

„Hello, my name is Nicolás Smith-Sánchez. I am a Spanish marine biologist currently doing my PhD at GEOMAR, researching the potential ecosystem and food web structure changes that could be induced by Ocean Alkalinization, a nature-based Negative Emissions Technology (NET). I also worked for project CUSCO in Perú.

As you might find out if you go through my gallery and read the stories behind each illustration, my studies and work often pour into my art in one way or another. Research gave me the tools to understand a world that fascinated me since I was a child. Back then, kneeling down by the tide pools and overturning rocks, I felt a rush of excitement, of anticipation, for what I might discover. Today I find that this natural passion materializes itself in my drawings.

As I curated the exhibition, I realized each piece provides a small window into different times from the last three years of my life, beginning when I first arrived in Kiel to study my masters in biological oceanography at GEOMAR. In order to give the viewer a thread to follow, I organized the pieces according to the geographical region in which the course or project that inspired them took place: South America, Asia and Europe. I hope you enjoy it.“

Nicolás Smith-Sánchez –

Lernt Nicolás und seine Arbeit noch mehr kennen:

Ihr findet weitere Arbeiten, auch fotografische, auf seinem Instagram Accout: @nicsmithsan

Hier geht es zu einem ausführlichen Ocean Stories Interview zum Thema Wissenschaft trifft Kunst / Lets get to know more about Nicolás and his work and watch the Ocean Stories Interview dealing with the subject „Science meets art“:

Click here to slide through Nicolás artworks

Scroll down to read the stories behind the art

Süd Amerika / South America

Simplified Humboldt Upwelling system food web

Aquarelle of a simplified Humboldt Upwelling system food web. On my third mesocosm campaign we travelled halfway across the world to Peru to study Climate Change-induced shifts in the intensity and seasonality of natural upwelling. Life is explosive here. One day, we took the vessel IMARPE VI out to the continental shelf break in order to fish for large zooplankton to introduce in our mesocosms. Shoals of Peruvian anchovy broke the surface ahead of our boat, escaping tuna hunting them from below. Inca terns would rest on the masts of the boat, taking off and darting into the shoals together with cormorants and pelicans and terns. A sea lion’s head would pop out on occasion, and off into the horizon humpback whales would blow jets of water up into the sky. That night, as we returned to harbor, we laid on top of the water coolers containing the catch for the day and just gazed up into the pitch black, thousands of stars returning our glance. And I just remember thinking how lucky I was to have been witness to such beauty.

Some birds of La Punta

Aquarelle of some of the birds that lived alongside us during our stay in La Punta, Lima. Time in La Punta for me was paced by the birds. Early in the morning the blackbirds sang loudly and a single hummingbird, which seemed to have made of the hostel’s garden its territory, would zoom amongst the Ibiscus flowers. As I walked out of the marine research institute (IMARPE) at noon, making my way to the market to eat some ceviche or arroz con pollo, the vultures or gallinazos stood perched on every electricity post, glaring down at the streets as the sun burned high above. In the afternoon, when I would make my way to the Club Nautico laboratory, the blue-eyed cocolís pecked the green grass for seeds, fluttering and flying around. At sunset, returning back to the hostel, I would look up at the branches of the trees to find the blue tanager. Another day gone.

Sardina pilchardus

Aquarelle of the common sardine (Sardina pilchardus) and the Peruvian anchovy (Engraulis ringens). The iridescence in these small pelagics, fishes that we normally do not think worthy of a second glance, is a true marvel. But beyond their beauty, they are crucial to the functioning, diversity and productivity of some of the most astonishing ecosystems in our oceans, the eastern boundary upwelling regions.

Larosterna inca

Aquarelle of the Inca tern (Larosterna inca). Also inspired by the mesocosm experiment in Peru, this piece was special to me because I tried to reproduce the dark plumage of this marine bird without using the color black. Many nature illustrators claim that black is not a color that exists in nature, but rather rises from the superposition of different tones.

Asien / Asia

Coryphaena hippurus

Aquarelle of a Mahi Mahi (Coryphaena hippurus). The first time I saw this other-worldly fish, it was riding off the wake of our boat on the way to field sampling in Guishan Island, off northeastern Taiwan. Off this island is a shallow hydrothermal vent system that over the course of one year underwent two major catastrophic events: an earthquake and a typhoon. The research group with whom I went here was interested in studying how the benthic community around these vents recovered, and whether the food web structure and its fundamental energy source had changed.

Beryx mollis

Aquarelle of Beryx mollis. We returned from Guishan Island loaded with biological samples. The postdoc in the team, our Taiwanese PhD colleague and I had many hours of lab work ahead to get those samples ready for storage, transport back to Germany and further processing, but we had come up with a plan. We worked our hands, eyes and buts off in the lab that day, and finally finished by midnight. Just in time to grab a bite at the Keelung market before venturing into the fish market, which opened around 1AM. Once we set a foot there I just could not stop running off in every direction, discovering new, odd fishes at every stand. I was overwhelmed with the excitement of what I was going to find around each corner. Sharks, oarfish, parrotfishes, red and orange-spotted groupers, trumpetfishes, moonfishes. I was marveled and saddened at the same time. Marveled by the diversity, the endless possibilities that nature has configured over thousands of year of adaptation and evolution; saddened by the scale of extraction and exploitation, by seeing all that dead beauty so out of place, faintly illuminated by the orange street lights and neon signs.

Europa / Europe

Korsika / Corsica

Thalassoma pavo, Chromis chromis and Symphodus mediterraneus

Aquarelle of three common western Mediterranean fish species (Thalassoma pavo, Chromis chromis and Symphodus mediterraneus). One of the practical courses during my master’s degree at GEOMAR took us to Corsica, where we learned about Mediterranean coastal ecosystems and carried out a little project on sea urchin development. But I think what I will remember about those two weeks is how happy we all were, how carefree. There are so many memories from those days that come to mind when I see this sketch. The seawater tasted especially salty and felt particularly cool early in the mornings when everyone was still sleeping and everything was bathed in a pale pink light. During the day it was hot and humid, bright clouds towered over the sea across the bay, and the t-shirt fabric stuck on us like a second skin. In the nights we would jump into the sea, dive masks on, plunging as deep as we could into the dark to gaze at the green sparks of bioluminescence.

Deutschland / Germany

Nerophis ophidion

Aquarelle of the straightnose pipefish (Nerophis ophidion). Another of the master’s practical work took me snorkelling in the Baltic seagrass meadows for pipefish. The evolutionary biology group at GEOMAR is interested in this model organism because they are one of the few vertebrate species in which pregnancy occurs in the males, providing a good opportunity to disentangle genetic and ambient determinants in development.

Bretagne

Phalacrocorax carbo and the European shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis

Aquarelle of the Great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) and the European shag (P. aristotelis). During the early fall of 2018 I spent some weeks at a summer school in Bretagne, where I spent the days looking through the scope and learning the wonders of larval fishes; the array of strategies, from curious behaviors to extraordinary body shapes, they deploy to survive through such a critical stage of their lives. In my free time I would turn rocks in the intertidal and look at the sea birds. Cormorants flew about often, or stood stoic on some distant rock drying their wings before another fishing incursion.

Haematopus ostralegus

Aquarelle of an Oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus), another common sight in Bretagne (and also back home in Kiel).

Kanarische Inseln / Canary Islands

Simplified mesocosm food web

Aquarelle of a simplified mesocosm food web. The first mesocosm campaign I participated in took place in Gran Canaria, and over the course of seven weeks I followed up with the zooplankton community, seeing how it changed and responded to our artificial upwelling treatments. Artificial upwelling is another nature-based NET conceived to enhance ocean storage of CO₂, and/or increase productivity of nutrient-poor regions (such as the subtropical gyres, colloquially referred to as the ocean deserts).

Sparisoma cretense, Thalassoma pavo and Canthigaster capistratus

Aquarelle depicting three common fish species of the Canary Island coastal ecosystem: la Vieja (Sparisoma cretense), el Pejeverde (Thalassoma pavo) and la Gallinita (Canthigaster capistratus). During this first mesocosm campaign, I would jump into the water and free dive at the end of the day. Underwater, sounds got to me from far away and time was halted, and I was suspended and elevated by the salty water. Light reached me from far above, shaped by the waves that broke at the surface, blue, green and white. And seeing the fishes, dozens of shapes and colors, pass by getting on with their day, I felt bliss and contempt.

Oithona

Aquarelle of Oithona, a common copepod in the Canary waters. I still remember when I looked through the scope for the first time to take a closer look at the microscopic community that thrives around Gran Canaria. The diversity of forms, of colors, seemed unreal to me. I had never seen anything like it before, only in the illustrations by Ernst Haeckle; how can something so curious, so eccentric, so intricate, so beautiful, simply be?

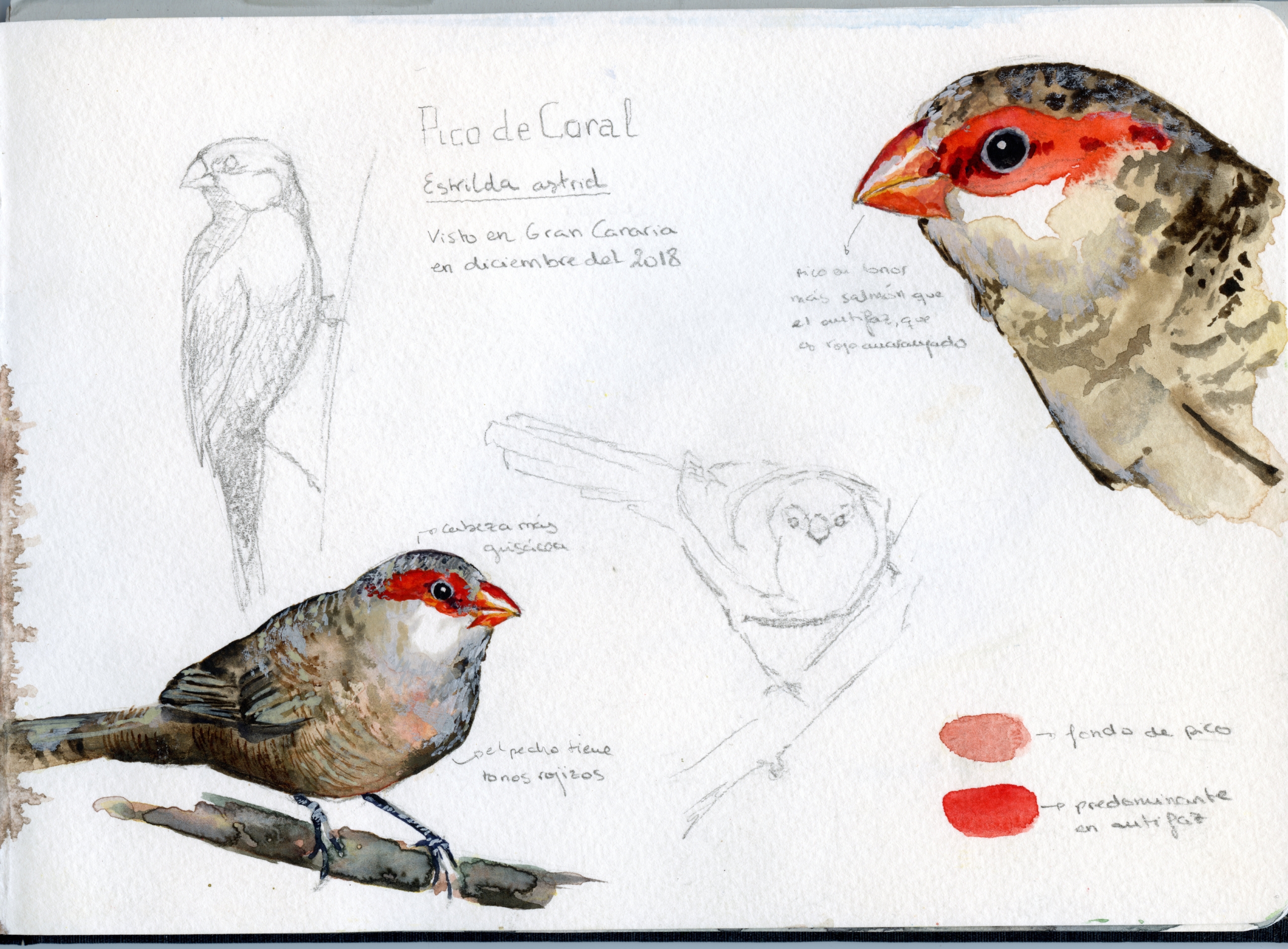

Estrilda astrild

Aquarelle of the Pico de Coral (Estrilda astrild), observed in Gran Canaria during the 2018 mesocosm campaign.

Temora and Centropages

Aquarelle of Temora and Centropages, two common copepods of our mesocosm community in Gran Canaria. On my second mesocosm field campaign, which also investigated responses to artificial upwelling in Gran Canaria, we deployed the small mesocosms in the Taliarte harbor. That year the plankton was less diverse than before, and these two zooplankters dominated, small but bulky, their stomachs full of green phytoplankton shining through their transparent bodies.

Island / Iceland

Uria aalge and lomvia

Aquarelle of the Common and Brünnich Guillemots (Uria aalge and lomvia, respectively), commissioned by project LOMVIA. In the summer of 2019 project LOMVIA took me to Iceland for 4 weeks. LOMVIA investigates the progressive shrinkage in the more Arctic Brünnich guillemot’s distribution, which is consistently retreating further and further north. This is hypothesized to be triggered by Climate Change, on one hand through changes in the ecological niche of the bird, which naturally feeds on krill at the ice edge, and on the other hand, and as a consequence of the latter, through increased competition with it’s more temperate cousin, the Common guillemot.

Common and Brünnich Guillemots nesting on the cliff

Aquarelle of Common and Brünnich Guillemots nesting on the cliff ledges at some of the bird colonies that we visited that summer.

Gadus morhua

Aquarelle of the Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua), a generalist predator in coastal and off-shore waters around Iceland. During the field campaign we visited harbors all around coastal Iceland; we would walk into the fish factories and ask when the landings would arrive. Sometimes we found a friendly greeting and were offered coffee and cookies, other times they were dismissive. The factories were always cold and smelled of the strong stench of seawater and seafood and bleach. We would change into the rubber boots, put on gloves, a hair net and a full body suit to keep the fish processing area clean. Sometimes I also had to put on a “beard” net. I gutted over 200 cod that summer, the ones that were as big as me I had to hold up with both hands and still struggled. We collected liver and muscle tissue samples to analyze for amino-acid stable isotopes. This is a biochemical marker that can give us clues as to the main food sources for these fishes, thus helping us construct a biochemical map of the major energy sources around Iceland. Samples were also taken for the birds, so that when we compare the fish and bird signals against each other we can pin-point the guillemots’ energy sources.

Alca torda

Aquarelle of the Razorbills (Alca torda), a cousin of the puffins; another common bird found at the cliffs of nesting guillemots.

Lockdown – Paintings from home

Chlorostilbon lucidus

Aquarelle of a Besourinho-de-bico-vermelho (Chlorostilbon lucidus). During the second COVID lockdown this past winter, the first experimental campaign of my PhD was postponed and the near future looked grim. To cheer myself up and turn the white walls of my room, and my mind, more colorful, I began to paint hummingbirds. This was one of them.

Landespolizei Schleswig-Holstein

Landespolizei Schleswig-Holstein